That tree.

That haggard and lonely tree, thrusting upward from its barren perch.

That life-thirsting tree, whispering to me from its encrusted roots: “Despite all…I am still here.”

The image of that tree is what compels me to write this. It resounds deep in the lost mines of my memory…to those moments when I heard Martha’s silent, disturbed presence whispering to me midway through our 17-year odyssey. She no longer could walk or talk or take care of herself. And yet I knew. I knew that despite all appearances, something deep within Martha was still here. All but hidden to my physical senses, life still stirred within my wife…“I am still here.”

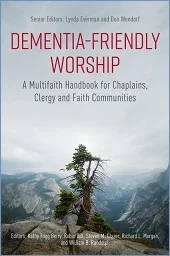

This cover photo of Dementia-Friendly Worship is so reflective of the book’s foundational theme: No matter what stage of dementia a person may be in, early or advanced, communicative or not, no one—NO ONE—is ever an “empty shell.”

This perspective flies in the face of popular opinion—if the mind is gone, the person is gone. That was the common view when Martha was diagnosed with early onset Alzheimer’s in 1997, three weeks after turning fifty.

It still is today, but that may be changing somewhat. Dementia-Friendly Worship has the potential to help melt this icy stigma.

“… in spite of the cognitive and other limitations imposed by dementias, the essence of the person, their core, their soul, is still there, very much alive,” say this book’s senior editors, Lynda Everman and Dr. Don Wendorf, PsyD, retired psychologist. “It’s so easy to focus on what people with dementia can no longer do; it is of utmost importance—not to mention inspirational, transformative, and redemptive—to observe what they still can do. And are doing!”

“But we have to be receptive to it,” says Don.

Cover design: Ian James Ross @sheffgraph

Dr. Daniel C. Potts, neurologist, puts it another way: “Of all the losses associated with dementia, I believe the greatest loss is that of relationship…What fuels the toxicity of this stigma, of this pulling away? I believe it is our failure to recognize and honor the inherent personhood of every human being, regardless of conditions or circumstances.”

For all these reasons and more, Don and Lynda say they originally preferred this book to be titled Souls Shine Forth. (But they discovered, as did I with my book, authors and editors don’t always have the last say.)

Based on all that I’ve read, this is a one-of-a-kind book. Its collection of insights is described as “a multi-faith handbook for chaplains, clergy, and faith communities.” It draws from 48 contributors/editors who come from a variety of traditions: Judaism, Islam, Christianity, Buddhism, Sikhism, and Native American.

Dementia, after all, is not prejudiced against any religion or faith or spiritual belief. Even agnostics and atheists are gazed upon with equal regard. This book’s contributors are all dementia advocates in one form or another. (I’m honored to be among this select group with a chapter titled “The Intimate Touch of Meditative Prayer.”)

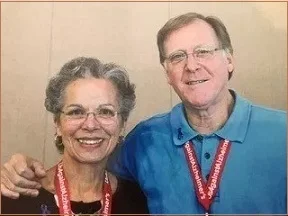

“We use the word ‘faith’ broadly,” says Lynda. “This book is for anyone who believes in a power beyond themselves.” You may remember Lynda from an earlier post as one of the two catalysts for bringing the Alzheimer’s postal stamp to fruition. She and husband Don collaborated with UsAgainstAlzheimer’s to make Dementia-Friendly Worship a reality. (Lynda and Don found each other “through our caregiving experiences and advocacy.” In previous lives, the two served more than four decades between them as full- or part-time caregivers for family members in one stage of illness or another.)

Lynda Everman and Dr. Don Wendorf

Until recently, the influence of spiritual issues on those living with Alzheimer’s and dementia and their caregivers had rarely been part of the public conversation. Most research focused on finding a physical cure while the majority of books are caregiver guidebooks or memoirs—all important, of course.

So it took me awhile after Martha’s diagnosis to understand that a crisis like Alzheimer’s—any serious crisis really—can carry some heavy emotional and spiritual baggage, as I’ve discussed before. Stuff like resentments, fears, unforgiveness, depression, anxiety, and obsessions. Which I discovered had to be addressed as best we could if Martha, our children, and I wanted any sense of wholeness and wellbeing. I share this in my book, A Path Revealed, in which Alzheimer’s is not the focus, it’s the context. The focus is the spiritual odyssey that unfolded before us over 17 years, and continues today.

No doubt, Dementia-Friendly Worship is for chaplains, clergy, and faith communities as the subtitle indicates. But it’s also for the friends and family of those living with Alzheimer’s and dementia, their caregivers. That’s easy to see as you thumb through its pages. This is a book to be fully read, though not necessarily front to back. It’s to be read in bite-sized chunks rather than in one sitting. There’s too much to process here as you reflect on your own experiences. It’s also a book to be referred to often.

As Lynda urges: If you are by tradition, say, a Methodist, don’t just look for Methodist contributors—you’ll miss too many valuable experiences from all the traditions represented here. Topics with invaluable insights range from “A Prayer for Forgotten Souls” to “Worship Brainstorming”; from “Seeing the Spirit Through Dementia: a Sikh Dharma Perspective” to “The Sacred Circle of Life: Native Americans and Dementia”; and from “Devotions in the Respite Care Setting” to “African Americans’ Old Timers’ Day.”

A powerful section is “Voices of Persons Living with Dementia”. Listen to Greg O’Brien, an award-winning journalist: “And so it is with control. I’ve learned through my disease that one relinquishes control to gain control at the foot of a higher power. That’s the blessing of the disease…Many (spiritual leaders) don’t fully comprehend dementia; like most of us, the word literally scares the hell out of them, a biblical demon howling in the desert, or many perhaps opt for the simple drive-by—a smile, a handshake, ‘hi ya,’ a handoff of a scriptural verse, a reassuring word, or a blank stare—then off to work the flock at large…”

Or this by Jim Gulley, a former scientist with the Goddard Space Flight Center who also lives with Alzheimer’s: “There are many ways pastors and parishioners can be helpful to persons living with dementia and their families. Education is key…Most of us don’t know how to communicate with persons who have cognitive impairments…Rather than preach at us, my observation is that effective chaplains and clergy listen carefully. They actively listen…”

An intriguing perspective is shared by Rev.Tim Langdell, both a Zen Buddhist priest and an ecumenical Catholic priest: “A key symptom of Alzheimer’s, although it isn’t always framed in this way, is that these patients are in a real sense more in the present moment than we usually are…they may delight in observing something…as if they are seeing it for the first time, over and over again. In a young child we often talk of this as being a ‘child’s sense of wonder.’ Perhaps we should see it the same way with our Alzheimer’s patients.”

I immediately recalled when Martha and I were waiting for a flight. We were among the last to board and Martha got tired of waiting. So she popped up and started jibber-jabbering with two puzzled attendants. I quickly explained our situation, at which point each attendant grabbed Martha and marched arm-in-arm with her down the runway to the plane, all while Martha was “talking” and laughing, enjoying every minute. I could only follow, shaking my head and smiling. And being grateful that these two attendants were so spontaneous in that moment.

Martha’s self-portrait three years into Alzheimer’s (She’d never painted before)

Worship should be WITH persons of dementia rather than FOR them, say United Methodist Bishop Ken Carder, now retired, and Norma Smith Sessions, an American Baptist. With such an approach “people with neuro-cognitive impairments not only are included, but their gifts are incorporated into the worship experience. This involves special sensitivity, inordinate flexibility, and spontaneous creativity among worship leaders.”

‘With’—not ‘for’—is a guiding principle for many of this book’s contributors. And it’s a meaningful guide for any care partner to follow: to be involved with your loved one as much as possible rather than always trying to do for them. It took me several years to get that and when I did, my interaction with Martha began to flow more easily.

“Someone offering a spiritual connection to a patient would do well to engage their own spiritual centering—whether it be prayer, meditation, or chanting—prior to each meeting with the patient,” say Rev. Allison Draper, M.Div., and Rev. Dr. Grace Schireson, both Zen Buddhist. “From an open-minded, judgment-free view, one can more readily experience the patient’s level of well-being or anxiety…One can quietly observe non-verbal cues: changing facial expression, respiration rate, skin tone, voluntary and involuntary hand gestures, and tone of voice.”

Rev. Theresa M. Brion, Episcopalian, shares that same sensitivity with this short-hand version: “Be open. Be humble. Be adaptable. And definitely laugh!”

Muslim Chaplain Maria Khani offers this insight: “Throughout my years of chaplaincy working with inmates, I have encountered those who were incarcerated physically and those who were incarcerated physically and mentally. The most challenging…however, are those who have been incarcerated physically, mentally, and spiritually.”

“Those who struggle with dementia and those who are incarcerated live in a dark world. They are isolated from their loved ones and fear overwhelms them, making it even more difficult to cope with their surroundings…A prayer is a state of humility in the presence of the Lord…(and) is indeed powerful enough to reach souls, minds, and hearts in moments where nothing else can touch them.”

That echoes my visits with Martha at the Menorah Manor nursing home in St. Petersburg when she often would be agitated, curled up in a fetal position in her bed or chair, her arm tucked behind her neck. I would sit beside her, slip my hand into hers, and begin to whisper our phrase or mantra that we’d learned years earlier through our Christian meditative practice. More often than not, she would relax after a while and straighten her body, at times looking at me or around the room. Other times she fell asleep as a profound stillness often would fill Martha’s room.

For the residents of Miami Jewish Health, Rabbi Israel de la Piedra says, “The prayers and songs comprise only one element of the weekly Shabbat service for those affected with dementia. In addition, a key component is the personal attention given to the residents by the rabbi. Before the service, the rabbi goes around the room greeting every person present…drawing heavily on issues that the rabbi knows are important to each resident and include frequent and loving, touching gestures.”

“There is a saying among those of us who work with persons of dementia: ‘Music is the last thing to go’, say Rev. David J. Fetterman, United Methodist, and Rev.Dr. Richard Morgan, Presbyterian Church, USA. “Music has the power to evoke memories…Helen was 86 and suffering from Alzheimer’s disease. She rarely spoke. Her short-term memory was around 30 seconds. While we were singing ‘Blessed Assurance’ she began to move her lips and then sing, clearly articulating the words. Caregivers were astonished to hear her sing. Apparently the music had reached beyond the dementia to her soul.”

Rabbi Cary D. Kozberg discusses how those with dementia and their caregivers can become strangers living among us. It’s vital to make them feel comfortable and loved, he says, quoting Leviticus 19:33-34: “If a stranger sojourns in your land, you shall do him no wrong…you shall love him as yourself, for you too were strangers once in the land of Egypt.”

What a strong resonance with our 17-year experience. You may have heard me describe why I call those years our odyssey rather than a journey. To me, “journey” sounds too tame and too planned for a crisis like Alzheimer’s. In the classical sense of “odyssey” you wake up one day unexpectedly in a foreign land. You’re lost, you’re hurt, and you’re confused. You want to get back home. You’ll go anywhere and do anything to get home. And when you do get home—IF you do—you find that home is not the same place as when you left. And you’re not the same person.

Bishop Ken Carder closes Dementia-Friendly Worship with this: “The expressions of love change, but the reality endures…(My wife) Linda no longer comprehends the word ‘love.’ Yet she expresses and responds to love! Language now fails her; but gentle touch, brushing her hair, a smile assures her of value and worth. She can no longer feed herself, so slowly placing food in her mouth becomes a sacrament of love. Love is not sentimentalism or warm fuzzy feelings. It is entering into the messiness, anguish, resistance, and hostility of the beloved with a non-anxious, gentle presence.”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

These are a few of the many meaningful threads that can be drawn from this book, and some of the memories they in turn drew from me. The wisdom and hard-won insights that fill the pages of Dementia-Friendly Worship are priceless.

Any cleric would do well to have at least one copy of this book at the ready, whether they are in a church, a synagogue, a temple, an assisted living facility, a veteran’s facility, a nursing home, a prison, or a mission field. And every seminary would be smart to make this book required reading for its pastoral care studies. Finally, Dementia-Friendly Worship isn’t a typical caregiver’s guidebook, but it certainly would be a worthy complement to those you now rely on.

Thank you, UsAgainstAlzheimer’s and your editors and contributors, for realizing the value of this book and for making it a reality.

Don, Michael, Lynda

By the way, the cover photo is by Michael J. Powell, Lynda Everman’s late son, taken on a trip with Lynda and Don to Yosemite. “He was quite the outdoorsman and mountain climber…and photographer,” she says with more than a touch of pride.

Thank you,

Carlen Maddux

www.carlenmaddux.com

carlen@carlenmaddux.com

PS1 September is World Alzheimer’s Month. You can commemorate it in at least two ways: (1)First, help your faith community leaders become aware of Dementia-Friendly Worship by forwarding this post to them. Or why not buy the book for them? If you or your organization would like to order multiple copies, email me (Subject line: Dementia-Friendly Worship) and I will send you the contact info. (Note: I have no financial interest in this book.) (2) Also, buy a sheet of the Alzheimer’s first-class stamps, or more, at 65 cents a stamp. The net proceeds from its sales go to the National Institutes of Health for Alzheimer’s research. As of July, over 7.1-million stamps have been sold, raising $953,000. Join me and thousands of others to Help Stamp Out Alzheimer’s.

PS2 My book, A Path Revealed: How Hope, Love, and Joy Found Us Deep in a Maze Called Alzheimer’s, can be ordered from any bookstore or found on Amazon.

PS3 As usual, feel free to forward this post to your friends and family. If you’d like to sign up for my blog, there’s no charge; just click here.