“Patients tend to move along the path of their expectations, whether on the upside or the downside.”

That’s a conclusion drawn by Norman Cousins after spending ten years on the staff of UCLA’s medical school. Cousins wrote about this experience in Head First: The Biology of Hope.

A second conclusion: “A strong will to live, along with other positive emotions—faith, love, purpose, determination, humor—are bio-chemical realities that can affect the environment of medical care. The positive emotions are no less a physiological factor on the upside than are the negative emotions on the downside.”

These observations by the late editor of Saturday Review magazine are lifted from notes in the opening pages of my journal, which I began keeping shortly after my wife Martha was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in September 1997.

Rather than try to wrap up my thoughts in a cohesive theme, I thought it might be interesting for you to read some of my journal’s raw notes as Martha and I moved forward. The notes here are from October 1997, after our friend Rev. Lacy Harwell encouraged us to visit his friend at the Sisters of Loretto in Kentucky.

You may remember that while visiting Sister Elaine we also traveled nearby to the Abbey of Gethsemani and stumbled upon Father Matthew Kelty, whom Martha and I heard and met with over three days. These notes are from our time there:

“Suffering has something to do with salvation. We know that much,” Fr. Matthew said in one of his homilies. “To say anything more is dangerous.”

This poet-monk suggested we read together, aloud, from the “Immortal Poems of the English Language.”

After Martha met privately with Fr. Matthew, he told us that suffering and illness offer no easy answer for why they occur. “This is now a spiritual journey,” he said while standing with us in the monastery library. “Don’t go bitter; draw on faith’s deepest strength. Drink deep from God’s well. It’s his gift.”

He suggested that when Martha returned home she set aside a time for silence away from the house, in a favorite church or solitary spot. He also told Martha to take one of the monastery’s Psalters and use it as a devotional. The Psalter is the book of Psalms set to music akin to a Gregorian chant. Finally, Fr. Matthew looked straight into Martha’s eyes and said: “You came calling on me. You are now one of us. So from now on, you are in my prayer.”

After Fr. Matthew left, Martha had difficulty explaining to me all they discussed during their private conversation. But I could tell that whatever it was, it was meaningful. For the first time in weeks, Martha’s face appeared relaxed. She carried herself with an air of confidence, as though she were saying, “I know something that you don’t.” Her eyes were as clear and blue as I’ve ever seen. Martha called Fr. Matthew “my new friend.”

Loretto Motherhouse--Nerinx KY Photo by Patricia Drury

During our time with Sister Elaine, she suggested: “You may want to look into the difference between willfulness and willingness. Examine your lives along these lines.” She pointed us to a book by Dr. Gerald G. May: Will and Spirit: A Contemplative Psychology.

Note to myself: I don’t have a clue as to what Sr. Elaine is getting at with this “willfulness and willingness.” I don’t think Martha does either. (Yet as I look back over this 17-year journey, this theme kept surfacing along the way: Am I willing or am I being willful? It still does).

“Learning to trust God is your goal,” Sr. Elaine told us toward the end of our visit. She suggested structuring a set of daily disciplines or practices:

Realize that our foundation is a growing relationship with God.

Help provide emotional reinforcement for Martha.

Mental and physical exercises.

Look into alternative healing practices.

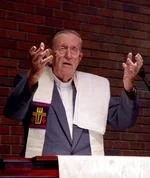

Rev. Lacy Harwell

We met with Lacy again shortly after returning from Kentucky, and shared our experiences with him. These were his observations:

Our program is sufficient—we must now work it.

Contemplative prayer depends on two things: Persistence and humility—not being articulate; not good works; not wealth; not good looks. Protestants have no contemplative prayer tradition, Lacy says. For this, he had to turn to the Catholics, who have a rich heritage.

Don’t become obsessed with Alzheimer’s. Do all that we know to do; give the disease to God; get into things Martha enjoys; move on with life.

Help Martha visualize herself in her favorite setting; visualize turning Alzheimer’s over to God.

Re. Martha telling her parents, ask Christ Jesus: a) to prepare them to receive the news; b) to show Martha the right time to tell them; and c) when we tell them, “You must get an absolute commitment to confidentiality. Only Martha can tell someone!!”

Finally, Lacy picked up on Fr. Matthew’s point about “suffering has something to do with salvation…” Lacy: “Something ‘beautiful’ will come out of this Alzheimer’s—be ready and watch for God’s hand.”

As we prepared to leave Loretto, Sr. Elaine shared an ancient description of contemplative prayer from the Eastern Church: “Fold the wings of your mind. Put your mind in your heart. Come into the presence of God.”

As you can see, the advice we received in late 1997 along with my thoughts about how to proceed were scattered—and tentative, as I remember. But these ideas were good, and they needed time to take root.

Reviewing and sharing these raw notes today has refreshed me. I hope you find something meaningful here as well.

Thank you,

Carlen

www.carlenmaddux.com

P.S. I know you get tired of seeing this, but we do have new readers coming aboard all the time. So feel free to pass this post along to your family and friends, who may sign up for my free weekly newsletter here.